Inherently, agricultural and outdoor workers experience a greater risk of mosquito bites that can vector illnesses such as chikungunya, dengue, Japanese encephalitis, West Nile, and Zika virus disease. The CDC and EPA recommend using EPA-registered insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus, or para-menthane-diol to protect workers against these infections. Fact sheets and posters have been released by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) outlining the Zika virus to promote education and communication regarding practices to reduce worker exposure.

Insect Related Diseases

Tick-Bite-Induced Red Meat Allergy

Nancy C. Hinkle, Ph.D., University of Georgia

Nancy C. Hinkle, Ph.D., University of Georgia

Extension staff are not physicians (nor do we portray them on television), but we can contribute to better health among Georgia citizens. One emerging condition we want to keep in mind is red-meat allergy provoked by tick bites.

Yes, as strange as it sounds, being fed on by lone star ticks (the most common ticks in Georgia) can predispose some people to developing a severe food allergy, causing an itching skin rash, gastrointestinal upset, and trouble breathing several hours after consuming red meat (beef, pork, venison, lamb, etc. – but not poultry or fish). This condition has only recently been recognized and many physicians are not yet aware of it; likely we’ll see more in the media about this condition in the future as it becomes more widely recognized.

Meanwhile, if you know someone who experiences repeated episodes of severe hives (typically affecting the entire trunk) accompanied by nausea and/or diarrhea, recommend that they consult with their physician and raise the possibility of red meat allergy due to prior tick exposure. The accompanying life-threatening anaphylaxis and difficulty breathing can require an ER visit, so this is not a trivial condition. While testing for the condition is available only at select clinics, management of the condition is relatively simple, involving eliminating red meat from the diet.

Georgia Mosquito Control Association plans for threat of chikungunya virus next spring

Merritt Melancon is a news editor with the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

As Georgia’s mosquito season draws to a close, mosquito control professionals are looking back, evaluating the season and planning for the challenges they will face next spring.

What happens to West Nile Virus in the winter?

Where, oh where, does the virus go (in the winter)?

Dr. Rosmarie Kelly, Public Health Entomologist, Georgia Department of Public Health

It’s that time of year when those in mosquito surveillance and control think fondly of consistently cooler temperatures and eagerly await that first hard frost. Of course, this is already happening in some places up north. We may have to wait a while longer in here in Georgia. But that does bring to mind the question: Where do all the mosquitoes go once the colder weather arrives?

Mosquitoes, like all insects, are cold-blooded creatures. As a result, they are incapable of regulating body heat and their temperature is essentially the same as their surroundings. Mosquitoes function best at 80 F, become lethargic at 60 F, and cannot function below 50 F. In tropical areas, mosquitoes are active year round. In temperate climates, mosquitoes become inactive with the onset of cool weather and enter diapause (hibernation) to live through the winter. Diapause induction also requires a day length shorter than 12 hours light (more than 12 hours dark). All mosquitoes pass through four developmental stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult, and diapause can occur in any of these stages depending on the species.

- The Aedes and Ochlerotatus species, and some Culiseta species, lay eggs in dry or damp, low-lying areas or containers that are subject to flooding from accumulations of precipitation. Winter is passed in the egg stage, with hatching dependent on the presence of water, water temperature, and amounts of dissolved oxygen.

- Coquillettidia and Mansonia species, and some Culiseta species, have larval stages that overwinter, apparently without total loss of activity, restricting development to very permanent water bodies. These species renew development towards the adult stage once water temperatures begin to rise.

- Overwintering in Anopheles, Culex and some Culiseta species takes place in the adult stage by fertilized, non-blood-fed females. In general, these mosquitoes hide in cool, dark places waiting for temperatures to rise and days to lengthen before they seek out a blood meal and resume their lives.

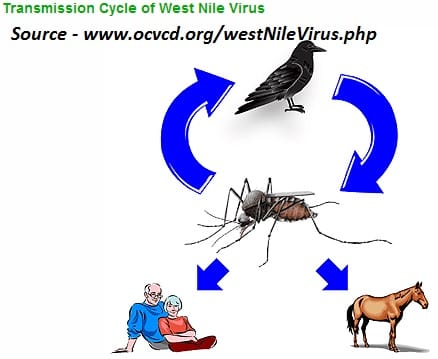

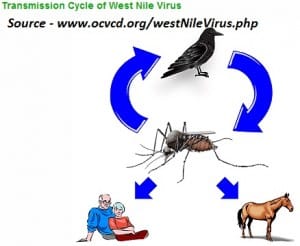

What, if anything, does this mean for West Nile virus (WNV)? If the mosquitoes are infected with WNV when they enter diapause, it should overwinter with them to be transmitted to birds when the mosquitoes emerge the following spring. Temperature is the crucial factor in the amplification of the virus. Studies in various states have shown that WNV does indeed overwinter in mosquitoes. The virus does not replicate within the mosquito at lower temperatures, but is available to begin replication when temperatures increase. This corresponds with the beginning of the nesting period of birds and the presence of young birds. Circulation of virus in the bird populations allows the virus to amplify until sufficient virus is present in the mosquito populations (and vector mosquito populations are high enough) that horse and human infections begin to be detected.

In the Northeastern U.S., Culex pipiens, the northern house mosquito, is the most important vector species. This species overwinters as an adult, and has been found harboring WNV during the winter months. This mosquito goes into physiological diapauses (akin to hibernation) during the winter months, and while it may be active when temperatures get above 50°, it will not take a blood meal.

Culex quinquefasciatus, the southern house mosquito and the major vector for WNV in Georgia, also overwinters as an adult, and also goes into diapause when winter comes, and it is likely that this mosquito also harbors WNV throughout the winter months. However, the southern house mosquitoes go into more of a behavioral diapause when temperatures are below 50°, and are quite capable of taking a blood meal (and maybe transmitting WNV) when things warm up during the winter, which is not an unlikely occurrence here in Georgia especially as one goes further south. So, although the risk for WNV transmission in the south in the winter months is very low, it is certainly possible.

Tiger, tiger…Aedes albopictus

Taken from the April 10 issue of Dideebycha, newsletter of the Georgia Mosquito Control Association

Aedes albopictus was introduced into the Port of Houston in 1985 in shipments of used tires from northern Asia. Movement of tire casings has spread the species to more than 20 states since 1985.

The Asian tiger mosquito is a small black and white mosquito. The name “tiger mosquito” comes from its white and black color pattern. It has a white stripe running down the center of its head and back with white bands on the legs. These mosquitoes lay their eggs in water-filled natural and artificial containers like cavities in trees and old tires; they do not lay their eggs in ditches or marshes. The Asian tiger mosquito usually does not fly more than about ½ mile from its breeding site and generally flies a considerably shorter distance.

Aedes albopictus associates closely with people and is an aggressive, daytime biting mosquito. It is native to the tropical and subtropical areas of Southeast Asia, and is now found in 1/3 of the Unites States. New Jersey, southern New York, and Pennsylvania are currently the northernmost boundary of established Ae albopictus populations in the eastern United States.

The tiger mosquito is an important disease carrier in Asia. In North America, Ae albopictus is among the most efficient bridge vectors of WNV. In addition to vectoring exotic arboviruses, this species can also transmit the endemic eastern equine encephalitis and La Crosse viruses in the laboratory and in the field. It is a competent vector of both Dengue and Chikungunya virus. In fact, Ae albopictus is a competent vector for at least 22 arboviruses.

A lot of work has been done recently on control of Ae albopictus. Since it is a daytime biting species and an asynchronous emerger, conventional truck-based ULV spraying doesn’t always work well. According to one study, an integrated pest management approach can affect abundances, but labor-intensive, costly source reduction is not enough usually to maintain Ae albopictus counts below a nuisance threshold.

References

Fonseca, et al, Area-wide management of Aedes albopictus. Part 2: Gauging the efficacy of traditional integrated pest control measures against urban container mosquitoes. 2013. Pest Management Science, 69 (12): 1351–1361.

Regulatory Restrictions Protect Human and Animal Health

Nancy C. Hinkle, Ph.D.

Veterinary Entomologist, Dept. of Entomology, University of Georgia

One of the foundations of Integrated Pest Management is prevention, and one of the essential underpinnings of prevention can be regulatory restrictions. If we prevent the introduction of a pest or disease into an area where it does not occur, we avoid the risks associated with the pest or pathogen.

Up until fifteen years ago we had never had a case of West Nile Virus in the U.S. So how did West Nile Virus come to North America? Probably someone smuggled in an infected bird that was carrying the virus. The smuggler didn’t think he was doing anything bad; after all, he had paid good money for the bird and wanted to bring it home with him to New York City. What was wrong with tucking the bird into his pants and not declaring it when the agent asked if he was bringing any living animals as he passed through Customs? Once home, the bird was placed in a cage near the apartment window, a local mosquito flew in and sucked a little of its blood, then flew out and fed on a local sparrow. The sparrow became infected with West Nile Virus, more mosquitoes fed on it and picked up the virus, and a few weeks later dozens of birds at the Bronx Zoo dropped dead of West Nile Virus after being fed on by these infected mosquitoes.

Up until fifteen years ago we had never had a case of West Nile Virus in the U.S. So how did West Nile Virus come to North America? Probably someone smuggled in an infected bird that was carrying the virus. The smuggler didn’t think he was doing anything bad; after all, he had paid good money for the bird and wanted to bring it home with him to New York City. What was wrong with tucking the bird into his pants and not declaring it when the agent asked if he was bringing any living animals as he passed through Customs? Once home, the bird was placed in a cage near the apartment window, a local mosquito flew in and sucked a little of its blood, then flew out and fed on a local sparrow. The sparrow became infected with West Nile Virus, more mosquitoes fed on it and picked up the virus, and a few weeks later dozens of birds at the Bronx Zoo dropped dead of West Nile Virus after being fed on by these infected mosquitoes.

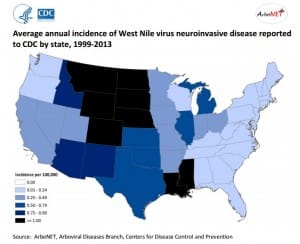

Meanwhile people in Queens were developing high fevers, severe headaches, and nerve problems like paralysis. Even though New York mobilized and started treating for mosquitoes, the virus was already established in birds and mosquitoes. West Nile did not exist in the U.S. prior to 1999; since that year mosquitoes have spread West Nile westward through the continental U.S., resulting in over 1,700 human deaths and ten times that many paralysis cases.

There is a reason the Customs Declaration Form that people entering the U.S. fill out contains the question, “Are you bringing with you meats, animals, or animal/wildlife products?” While we don’t often think about it, animals in other countries can contain pathogens that we don’t have here in North America and that can be lethal to humans or animal life on our continent. If these hosts get moved into our country, the pathogens can rapidly spread to local wildlife and then to humans.

Before traveling outside the U.S., travelers should visit the Centers for Disease Control website to determine which vaccinations and medications are needed for the areas to which they’ll be traveling. It’s important to follow appropriate precautions to avoid insect bites. And people reentering the U.S. should not bring back with them any living animal or plant, meat, or other animal products. The fellow who smuggled in the West Nile-infected bird had no idea that his action would result in the death of over 1,700 Americans, thousands of horses, and countless wild birds.

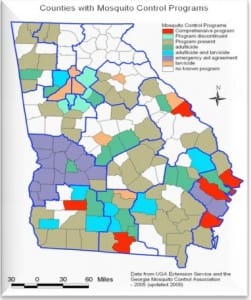

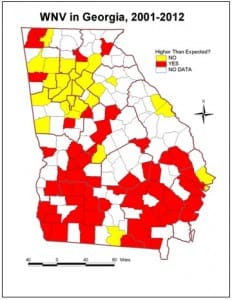

What is the relationship between WNV infection and mosquito control programs?

Answer: This study indicated that people in areas with no mosquito control program had a tenfold greater risk of WNV than those in areas where mosquitoes were controlled.

Read the entire article Using Mosquito Surveillance Data taken from the April 10, 2014 issue of Dideebycha, newsletter of the Georgia Mosquito Control Association

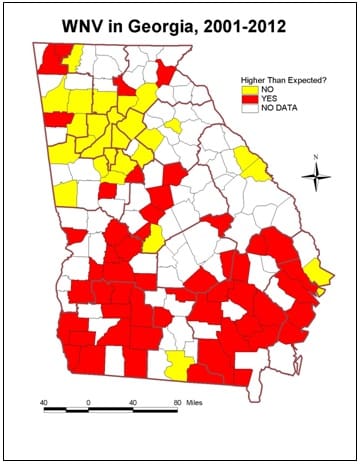

Mosquito surveillance is an important component of any mosquito control program. Where arboviral diseases occur, mosquito testing is an equally important component of an arboviral surveillance program. Arboviral encephalitis can be prevented in two major ways: personal protective measures to reduce contact with mosquitoes and public health measures to reduce the population of infected mosquitoes in the environment (mosquito control). Analysis of surveillance data provides information about the timing of arboviral transmission and the risk to the public, which can trigger county-level educational programs to help reduce risk.

Mosquito surveillance is an important component of any mosquito control program. Where arboviral diseases occur, mosquito testing is an equally important component of an arboviral surveillance program. Arboviral encephalitis can be prevented in two major ways: personal protective measures to reduce contact with mosquitoes and public health measures to reduce the population of infected mosquitoes in the environment (mosquito control). Analysis of surveillance data provides information about the timing of arboviral transmission and the risk to the public, which can trigger county-level educational programs to help reduce risk.

A study comparing two mosquito control districts showed that the program with the most mosquito surveillance and best documented larviciding and adulticiding operations had the fewest number of WNV cases. This study indicated that people in areas with no mosquito control program had a tenfold greater risk of WNV than those in areas where mosquitoes were controlled.

What are the roadblocks to arboviral surveillance in Georgia? We really do not have enough data to do good predictive calculating, particularly at the State level. Predicting where and when WNV outbreaks will occur is difficult, especially in areas with endemic transmission, which is what occurs in Georgia. Most of our sentinel data do not match up with our case data, as counties doing mosquito surveillance are not necessarily the same counties where human cases are occurring. Culex quinquefasciatus (Southern house mosquito), our primary WNV vector, are not evenly distributed, so neither is risk of human cases. However, we do not have sufficient surveillance to know where risk is occurring, and maintaining mosquito monitoring systems is costly even though it is essential according to the CDC.

Where data are available, the best predictor of risk is the Vector Index, the minimum infection rate (MIR) times the number of mosquitoes per trap night (abundance), which provides 2-4 weeks lead time in advance of human cases. Where adequate surveillance is maintained, this gives sufficient lead time to implement adult mosquito control efforts, which have demonstrated success in reducing human risk, resulting in fewer WNV cases (Carney, 2008).

Reference: Carney, R.M., Husted, S., Jean, C., Glaser, C., & Kramer, V. (2008). Efficacy of aerial spraying of mosquito adulticide in reducing incidence of West Nile Virus, California, 2005. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 14(5), 747–754.

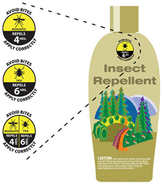

New Graphic Helps Consumers Make Informed Choices About Insect Repellents

Posted July 17, 2014 on the IPM in the South blog from the Southern Region IPM Center

The EPA unveiled a new graphic that will be available to appear on insect repellent product labels. The graphic will show consumers how many hours a product will repel mosquitoes and ticks when used as directed.

The EPA’s new graphic will do for bug repellents what SPF labeling did for sunscreens. This new graphic will help parents, hikers and the general public better protect themselves and their families from serious health threats caused by mosquitoes and ticks that carry debilitating diseases. Incidence of these diseases is on the rise. The CDC estimates that there are nearly 300,000 cases of Lyme disease in the United States each year. Effective insect repellents can protect against serious mosquito- and tick-borne diseases.

The EPA is accepting applications from manufacturers that wish to add the graphic to their repellent product labels. The public could see the graphic on products early next year.

First Chikungunya case acquired in the United States reported in Florida

Seven months after the mosquito-borne virus chikungunya was recognized in the Western Hemisphere, the first locally acquired case of the disease has surfaced in the continental United States. The case was reported today in Florida in a male who had not recently traveled outside the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is working closely with the Florida Department of Health to investigate how the patient contracted the virus; CDC will also monitor for additional locally acquired U.S. cases in the coming weeks and months.