Regulatory changes and sources of info for the Georgia pest control industries.

Willie Chance, UGA Center for Urban Agriculture

1. In January 2013 the U.S.-E.P.A. mandated some sweeping changes in the way pyrethroid-based insecticides will be used in the home environment. These changes will impact use labels for professional pest control operators and products available to homeowners in the over-the-counter market.

Pyrethroid insecticides can be recognized because the names of the active ingredients end in “-thrin” or “-ate”. Examples of commonly used pyrethroids are bifenthrin, cypermethrin, lambda-cyhalothrin, cyfluthrin, permethrin, esfenvalerate, etc. Pyrethroid products (sprays, aerosols, and granulars) are common in the professional market, and they dominate products in the over the counter (OTC) market.

Broadcast applications to large surfaces such as exterior walls of buildings, patios, or concrete walkways will no longer be allowed. Treat only where the pest is or will enter a structure (around windows, doors, or other openings). All outdoor applications must be limited to spot* or crack-and-crevice treatments only, except for the following permitted uses:

- Treatment to soil or vegetation around structures;

- Applications to lawns, turf, and other vegetation;

- Applications to the side of a building, up to a maximum of 3 feet above grade;

[*A spot treatment is not to exceed two square feet; making adjacent spot treatments to cover a large area is not allowed.] Pyrethroids used for termite pre-treatments have additional guidelines

See the complete Guidance Document from which this info is taken – http://tinyurl.com/lfxg6eg These regulations will also be on the pesticide label. Read and follow the label – it is the law!

2. Pesticide applicators must now verify residency during recertification. During the 2013 legislative session, a house bill was passed that required all state agencies that issue licenses to verify the legal residence of the applicant. See this article.

3. MSDS sheets should eventually be modified by OSHA and called SDS sheets. These SDS sheets will be used globally. Info taken from http://www.osha.gov/dsg/hazcom/HCSFactsheet.html

Major changes:

- Hazard classification: Chemical manufacturers and importers are required to determine the hazards of the chemicals they produce or import.

- Labels: Chemical manufacturers and importers must provide a label that includes a signal word, pictogram, hazard statement, and precautionary statement for each hazard class and category.

- Safety Data Sheets: The new format requires 16 specific sections, ensuring consistency in presentation of important protection information.

- Information and training: To facilitate understanding of the new system, the new standard requires that workers be trained by December 1, 2013 on the new label elements and safety data sheet format, in addition to the current training requirements. See https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3642.pdf

More information can be found on OSHA’s hazard communication safety and health topics page at www.osha.gov/dsg/hazcom/index.html. Note that these changes cover chemicals in general and does not replace existing pesticide labels and regulations.

Companies will want to:

4. Label changes for the neo-nicotinyl pesticides (examples include imidacloprid, dinotefuran, clothianidin and thiamethoxam) These are to protect bees and other pollinators. Watch labels for the Bee Advisory Box. For more information see this article.

Recent research indicates that contamination of flowers or nectar with these pesticides can lead to bee injury. Do not treat pre-bloom or blooming plants with these chemicals. Read the label for other information. This will help protect bees and help to keep these available to the industry. http://ugaurbanag.com/insecticide-application-timing-vital-to-native-bee-conservation/

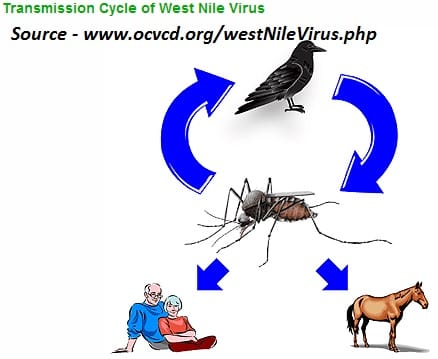

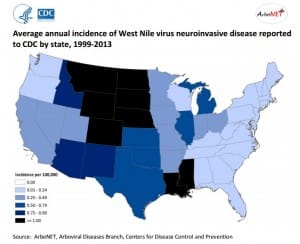

5. UGA has a video to help applicators prepare to take the Mosquito Control (Category 41) exam.

6. Georgia Clean Day is a program that gives an opportunity to discard old, unusable, or cancelled pesticides to a hazardous waste contractor for disposal. The Georgia Department of Agriculture has secured a limited amount of federal funds to revitalize the Georgia Clean Day Program for 2013. For more information or to find an event please contact Joshua Wiley (404-656-4958 or joshua.wiley@agr.georgia.gov) with the Department’s pesticide program.

7. Africanized bees have been discovered in Georgia. Though they look like traditional honey bees, when disturbed Africanized bees respond very aggressively and can kill or severely injure people who have not been trained in how to react to these bees. Everyone who works or spends much time outside should know how to deal with Africanized honeybees. See this article.

8. The GA Pest Management Handbook is updated annually with chemical and non-chemical pest control methods. It comes in a commercial and homeowner editions which can be purchased or viewed or downloaded as pdfs from http://www.ent.uga.edu/pmh/ See just the turf info or the new UGA turf app here –www.GeorgiaTurf.com.

9. UGA Apps to manage turf pests – http://blog.extension.uga.edu/urbanag/?p=581 or to identify invasive pests –http://apps.bugwood.org/apps.html

Online and other training

10. UGA Safety Makes Sense Landscape Worker Safety Certificate Course is available at no charge at vimeo.com/46623806. You can train on your time schedule, rainy day or any day. The training video (a compilation of the Safety Makes Sense series) can be viewed online or downloaded and saved for use when Internet is not available. The course includes Certificates of Completion.

The bilingual safety manual, Safety for Hispanic Landscape Workers, is available Online or for purchase All center safety training resources and Hispanic worker resources are available on the UGA Center for Urban Agriculture web site at Safety Makes Sense. This includes a series of short bilingual safety videos.

11. Monthly UGA webinar for landscape industry – http://ugaurbanag.com/webinars . Past classes are also online.

Also – Bi-monthly webinar for the structural pest control industry with credits – email Dan Suiter at dsuiter@uga.edu.

12. The Urban Ag Council has an excellent collection of Safety Zone training materials – http://www.maltamembers.com/safetyzone/. Part of this collection of training materials is the UAC Safety School.

13. Accessible Training for the Landscape & Turf Industries

Disposing of excess pesticides

Important Info for Landscape and Turf Pesticide Applicators

14. eXtension is a web-based collaboration of US land-grant universities to make university educational resources more accessible – http://about.extension.org/

15. eLearn Urban Forestry Online Training – An online, distance-learning program geared specifically toward beginning urban foresters and those allied professionals working in urban landscapes. Offers International Society of Arboriculture and Society of American Foresters credit and a certificate program. Visit www.elearn.sref.info

Find this information in this article.