Paul Pugliese is the agriculture & natural resources agent for the University of Georgia Extension office in Bartow County.

An herbicide designed to kill weeds in turfgrass can also kill neighboring trees and shrubs.

Herbicides in the phenoxy chemical class provide broadleaf weed control in lawns, pastures and hay forages. Some of the more common chemicals in this class include 2,4-D; MCPP; dicamba; clopyralid; and triclopyr.

Safe for animals but not always for trees and shrubs

These chemicals are considered very safe and leave very few toxicity concerns for animals. In fact, many of these herbicides are labeled for pasture use and allow for livestock to continue grazing without any restrictions.

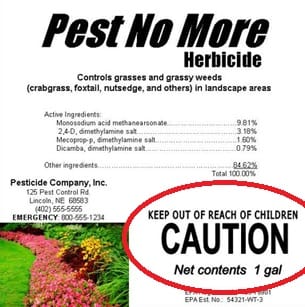

However, pesticide labels should always be read and followed to determine if any special precautions should be taken for specific site uses.

Phenoxy herbicides provide selective weed control, which means they control many broadleaf weeds without causing damage to grass. Of course, each product is a little different and some are labeled for very specific turfgrass types, depending on their tolerance.

The label should be checked for application to a specific lawn type (tall fescue, bermudagrass, zoysiagrass, etc.). If the turfgrass isn’t on the label, don’t assume the herbicide can be applied to all lawns.

Unfortunately, phenoxy herbicides don’t discriminate between dandelion weeds or any other broadleaf plants, including many trees and shrubs. So, it’s very important to take extra precautions when applying these herbicides near landscaped areas with ornamental plants.

Wind and rain can spread herbicides

Consider the potential for drift damage to nearby plants and avoid spraying herbicides on a windy day. There is also the potential for movement of these herbicides through runoff and leaching in the soil. This is why the product label usually warns against spraying within the root zone of trees and shrubs and never exceeding the maximum application rates listed on the label.

Many homeowners and landscapers often overlook these label precautions. The information that is contained on the label can seem somewhat vague to inexperienced applicators.

The biggest misconception concerns where the root zone of a tree or shrub exists. The roots of mature trees and shrubs actually extend well beyond the drip line of the canopy. Research shows that absorption roots may extend as much as two to three times the canopy width.

Consider spot-spraying to target individual weeds rather than broadcasting applications across the entire lawn. And never exceed the labeled rate.

In landscapes that contain mature trees and shrubs, phenoxy herbicides may not be the best choice for weed control. These herbicides may be best reserved for wide-open spaces such as athletic fields, parks and pastures where tree roots are at a safe distance.

The high potential for herbicide damage to trees is another great reason to protect tree roots by providing a mulch zone that extends well beyond the drip line of the canopy. If you’re not trying to grow a manicured lawn underneath a tree, then there is no reason to apply phenoxy herbicides there for weed control.

Use the right herbicide for the job

Another way to avoid potential damage is to rely less on phenoxy herbicides. Other classes of herbicides have less potential to affect the roots of nearby trees and shrubs. Take the time to identify your weeds and choose a more selective herbicide rather than combination products that usually contain multiple chemicals in the phenoxy class.

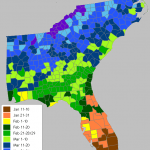

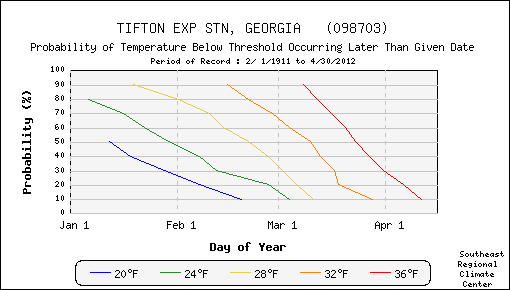

Many pre-emergent herbicides can prevent weed problems in lawns. The key is to apply them at the correct time in spring and fall. Applying too early or too late often provides inadequate weed control and requires additional herbicide applications. Rotating pre-emergent herbicide classes will avoid the potential for resistant weeds. Also, be sure to apply water to the area according to the pre-emergent herbicide’s label to activate it in the soil.

For more information about the effects of phenoxy herbicides on landscape trees and shrubs, view the UGA Center for Urban Agriculture webinar at ugaurbanag.com/webinars. For assistance with weed identification and specific herbicide recommendations, contact your local UGA Extension office at 1-800-ASK-UGA1 or visit www.Georgiaturf.com.

You can also watch an online webinar on Effects of Phenoxy Herbicides on Landscape Trees and Shrubs by Paul Pugliese.