Seven months after the mosquito-borne virus chikungunya was recognized in the Western Hemisphere, the first locally acquired case of the disease has surfaced in the continental United States. The case was reported today in Florida in a male who had not recently traveled outside the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is working closely with the Florida Department of Health to investigate how the patient contracted the virus; CDC will also monitor for additional locally acquired U.S. cases in the coming weeks and months.

Mosquitoes

Chikungunya Virus is Expected to Become Established in the U.S.

Reprinted from Entomology Today – Read the entire article here.

About six months ago, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control issued a travel warning for people visiting islands in the Caribbean because chikungunya virus had been detected on the island of St. Martin. This was the first time it had been detected in the Americas.

About six months ago, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control issued a travel warning for people visiting islands in the Caribbean because chikungunya virus had been detected on the island of St. Martin. This was the first time it had been detected in the Americas.

Now, in addition to the islands, health authorities are preparing for the virus to infect people in the U.S. itself.

“It’s not a matter of if, but when,” Dr. James Crowe, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University, recently said to USA Today.

According to the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), “it is virtually certain” that the virus will become established in the U.S. According to Paul Etkind, senior director for infectious diseases at NACCHO, “Local health departments should expect to see more of these cases as travel to the Caribbean for business and pleasure purposes increases over time. In addition, hundreds of thousands of soccer fans, many from the United States, are expected to travel to Brazil in July for the World Cup. The opportunities for introduction of the virus via infected fans returning from the games will be many.”

Chikungunya Virus, Is Georgia at Risk?

From the Georgia Mosquito Control Association newsletter – DIDEEBYCHA

In 2001, the CDC and the Pan American Health Organization jointly released a document entitled Preparedness and Response for Chikungunya Virus Introduction in the Americas. In late 2013, Chikungunya was found for the first time on islands in the Caribbean, where it has persisted and continued to spread.

Chikungunya fever is an emerging, mosquito-borne disease caused by the Chikungunya virus. It is transmitted predominantly by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, the same species involved in the transmission of dengue. Chikungunya is an RNA virus that belongs to the Alphavirus genus in the family Togaviridae. The name chikungunya derives from a word in Makonde and roughly means “that which bends,” describing the stooped appearance of persons suffering with the characteristic painful arthralgia.

Epidemics of fever, rash, and arthritis resembling CHIK were reported as early as the 1770s. However, the virus was not isolated from human serum and mosquitoes until an epidemic in Tanzania in 1952−1953. Subsequent outbreaks occurred in Africa and Asia, many of them affecting small or rural communities.

In Asia in the 1960s, CHIKV strains were isolated during large urban outbreaks in Bangkok, Thailand. These large outbreaks also occurred in Calcutta and Vellore, India, during the 1960s and 1970s. After the initial identification of CHIKV, sporadic outbreaks continued to occur, but little activity was reported after the mid-1980s. In 2004, however, an outbreak originating on the coast of Kenya subsequently spread to Comoros, La Réunion, and several other Indian Ocean islands in the following two years.

From the spring of 2004 to the summer of 2006, an estimated 500,000 cases had occurred. Since 2004, Chikungunya virus had been causing large epidemics of chikungunya fever, with considerable morbidity and suffering. The epidemics had crossed international borders and seas, and the virus had been introduced into at least 19 countries by travelers returning from affected areas. Because the virus had been introduced into geographic locations where the appropriate vectors are endemic, it was thought likely that the disease would establish itself in new areas of Europe and the Americas.

What about Georgia? There certainly is a risk of introduction and spread; there is no immunity and appropriate vectors and hosts exist here. McTighe and Vaidyanathan (2012. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, Vol. 12:867-871) tested the vector competency of Virginia and Georgia strains of Ae albopictus for CHIK virus and determined that they were all highly competent vectors of this virus. In their conclusions these last authors stated, “Only early and specific detection of human cases coordinated with vector control can reduce the risk of local transmission of CHIKV in the US.”

- High fever (103-104 F)

- Rash

- Severe incapacitating arthritis/arthralgia.

o Generalized

o Usually acute (several days to several weeks, though 20% of individuals have long-term joint complaints)

- Hemorrhagic manifestations have been reported (rare)

- Rarely if ever fatal – may cause encephalitis

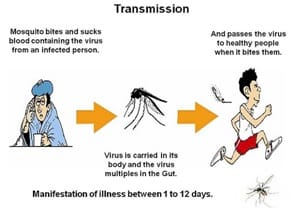

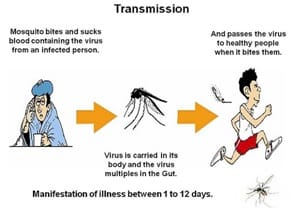

These symptoms appear on average 4 to 7 days (but can range from 1 to 12 days) after being bitten by an infected Aedes mosquito. Infected individuals develop a high titer viremia and can infect mosquitoes during this time period.

References

- http://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/

- http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs327/en/

- http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=9053&Itemid=39843

- http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)60185-9/fulltext

Controlling Adult Mosquitoes

Elmer Gray, UGA Entomologist

Adult mosquito control is a growing business. However, depending on the local environment, success can vary. The first technique in most mosquito control programs is eliminating or treating the water where mosquito larvae develop (larviciding). In addition, some homeowners are looking for help to kill adult mosquitoes (adulticiding).

As with any pest management program, identifying the pest is extremely important. Knowing the particular species of mosquito you are targeting will help operators locate the larval habitat and devise the most efficient plan of attack.

In support of this type work, Dr. Rosmarie Kelly from the GA Department of Public Health has offered mosquito identification classes in the past and plans to do so in 2014 if the budget permits. Watch the Pest Control Alerts training calendar for information on these and other trainings. Dr. Kelly may be able to help with identifying small numbers of mosquitoes if you cannot attend these classes. Also see the information on mosquito identification in this article.

By identifying the pest species and targeting the larval habitat first, companies can sell their program as operating in an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) manner. This is because these pesticide applicators target the pest in the most efficient manner even if that is by adulticiding. In some areas of Georgia, there can be vast acreages of low lying, wet areas that create excellent larval mosquito habitat. In this case, the best operators can do on a small scale is to larvicide the closest larval habitats where mosquito larvae are present and then adulticide around the area you are trying to protect.

ULV Application

When trying to suppress the adult mosquitoes prior to an event, some type of Ultra Low Volume (ULV) sprayer can be very helpful. There are a variety of sizes available, from those that fit in the back of a pickup truck, which can be used for whole communities to handheld units for much smaller areas. There are also some that fit on 4-wheelers, which can be handy for a smaller operation.

Permethrin is still a good choice for ULV applications, but the whole range of products available is listed in the Commercial Pest Management Handbook. As with all pesticides, follow the label closely.

With small scale adulticiding, suppression of the pest population is usually temporary. Any of the products when used properly will kill the adult mosquitoes that come in contact with the aerosol produced by the ULV machines. However if there are large areas of larval habitat surrounding the site, more mosquitoes are coming. When significant mosquito populations are present, a Wednesday and Friday evening application may be needed to provide relief for a weekend event. From an environmental, ethical and economical standpoint; it is important to only apply pesticides when significant mosquito populations are present.

One technique that has been used for a long time to monitor adult mosquito populations is the “landing rate count”. The technique consists of counting the number of mosquitoes that land on a person in a given amount of time. Consistency is extremely important with this technique. It is best if one person conducts the evaluation at a specified site, at a similar time of day, wearing similar clothing. Dark blue coveralls (most biting flies are attracted to dark colors) can be used to standardize clothing and reduce the actual number of bites received. A typically protocol could involve an individual standing in a semi-protected area (out of the wind) for one minute, and then counting the number of mosquitoes landing on the front half of the body. Landing rate data is important when documenting the need for adulticide applications.

Timing ULV Applications

ULV adulticiding should not be conducted during the heat of the day, when the insecticide will be carried away from the mosquito habitats by heat radiating from the ground. Adulticiding should be conducted when there are temperature inversion conditions that hold the aerosol of insecticide droplets close to the ground where the mosquitoes are active. This is usually in the early morning and later in the evening when the ground cools and the air close to the ground is cooler than the air higher up.

Barrier Sprays

Another technique that has proven effective for adult mosquito suppression is barrier sprays. Applicators apply a uniform spray to vegetation, taking care to cover the undersides of the leaves where the mosquitoes rest during the heat of the day. The adult mosquitoes are killed when they contact the residual chemical. Any type of pressurized sprayer can be used. The active ingredient of choice for barrier sprays is bifenthrin, but permethrin and the other pyrethroids are effective as well.

Barrier sprays are particularly effective against the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, which is our most common mosquito pest throughout most of Georgia. (In coastal areas, the salt marsh mosquito is predominant). The Asian Tiger mosquito develops in containers during the heat of the summer and is described as a daytime biter. Consequently, it is difficult to use ULV applications for this pest, because the Asian tiger mosquitoes are not active after dusk when conditions are best for ULV operations. As a result, public education to encourage people to eliminate containers and standing water around their homes is extremely important, but realize that compliance is a concern.

West Nile Virus

The presence of West Nile Virus (WNV) has created more interest in mosquito control. Now there is a focus on the Southern House mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, which is the primary vector of WNV in the southeast. This species prefers to develop in nutrient rich waters, like waste lagoons and catch basins. When it gets dry, the water stands in the catch basins and storm drains and this species proliferates. This leads to confusion about wet and dry conditions. When the weather is wet, all the other mosquitoes do well. When it is dry and water stagnates in the storm drain system, the Southern House mosquito thrives and there is an increased risk of WNV transmission.

There has been a whole series of products developed for treating water in storm drains and catch basins, including Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis (Bti) and Bacillus sphaericus based products and a variety of methoprene formulations.

Pesticide Applicator Licensing for Mosquito Control

A couple years ago Georgia created a mosquito control category for certified pesticide applicators, Category 41 – Commercial Mosquito Control. Applicators that were already treating mosquitoes before this time under Category 31 (Public Health) are allowed to continue treating mosquitoes using their current license. New applicators should obtain a Category 41 license.

The training manual for Category 41 is very helpful, since it was created to be used as a resource for smaller operators. Order the Mosquito Pesticide Applicator study materials (Mosquito Biology, Surveillance and Control) at – http://www.caes.uga.edu/publications/for_sale.cfm

If an applicator wants to obtain a Category 41 license, there is also a video to help as they study the manual and prepare for the exam. Find the video at this website.

If any commercial companies are conducting large-scale mosquito control programs, they may need to file a Notice of Intent (NOI) for an NPDES permit. The website for the Georgia Mosquito Control Association (gamosquito.org) has information on permitting and is loaded with other relevant information.

(The Alerts editor wants to say ‘Thank you!’ to Dr. Rosemarie Kelly who reviewed and contributed to this article.)

New Online Video Helps Prepare Pesticide Applicators to Pass the Mosquito Control Exam

Elmer Gray, UGA Entomology Department

For pesticide applicators preparing to take the Mosquito Control Pesticide Applicators exam, help is as close as your computer!

Mosquito Control is a growing part of the landscape industry. Commercial applicators of mosquito control products need to have pesticide applicator certification in Category 41, Mosquito Control. UGA Entomologist Elmer Gray has recorded an online video to better prepare applicators to take and to pass the Category 41 pesticide exam.

The new video that helps to prepare applicators to take the Mosquito Control (Category 41) exam is posted online at http://www.gamosquito.org/training.html

Note that the video is a supplemental help to those studying for the exam and is not a replacement for studying the manual! Applicators should order and study the manual before taking the exam.

If the applicator has not already passed the general standards exam through the GA Dept of Ag Pesticide Division, they will also need to order that manual, study and also pass that exam as well.

Mosquito control certification is handled through the GA Dept of Ag Pesticide Division. We sent the following information earlier concerning the Pesticide Division, but include it here again so that you have all info together in case you want to pursue a license.

More information on the Mosquito Control exam and the Georgia Dept of Ag Pesticide Division

Note that the commercial mosquito pesticide applicator program is administered by the GA Department of Agriculture Pesticide Division, not the Structural Pest Control Division. Regulations and contacts for the Pesticide Division differ from those in the Structural Pest Division. This info will help guide you as you pursue this certification. You can also call GDA directly – (800) 282-5852.

Where can I order training manuals to study to take the commercial pesticide applicator exam (mosquito control, ornamentals and turf, etc.)?

If you do not already have a commercial license, you will need to take two exams – the General Standards exam and the exam specific for your field (Mosquito Control, Ornamentals & Turf, Right of Way, etc.) You can find information on ordering the manuals for the general standards exam and the category exams at this website – http://www.caes.uga.edu/publications/for_sale.cfm

How can I register to take a commercial pesticide applicator exam?

Visit this website – https://www.gapestexam.com/. You will need to create an account to enter the system. The exams are given at Technical Colleges across the state.

I have a license in one category from the Pesticide Division and want a license in a second category. Do I have to take the General Standards exam again?

No, you just need to take the test for that exam. Order the manual for that category, study the manual and then register for and take the exam that is specific for that category.

Where can I find pesticide applicator recertification classes?

Visit www.kellysolutions.com/GA/Applicators/Courses/CourseIndex.asp

Also contact your local Extension Agent for classes – http://extension.uga.edu/about/county/index.cfm

Where can I find information on my commercial applicator’s license (hours needed, etc), recertification classes available, etc.?

Visit this website – http://agr.georgia.gov/1pesticide-applicator-licensing-and-certification.aspx

The Georgia Department of Agriculture now has a Licensing Division. There are 7 coordinators with a call center to help assist with online renewals. The coordinators are being crossed trained so that everyone is familiar with the basic licensing process for each license. Contact the Licensing Division if you have questions – 404-586-1411 or toll free 855-424-5423 or email GDAlicensing@agr.georgia.gov

For regulatory questions continue to contact the respective division.

Sandy Shell is one of the Licensing Coordinators for the Georgia Department of Agriculture. She recommends the following website:

www.kellysolutions.com/ga The following can be accessed through this website:

- Verify credit hours for Commercial Pesticide Applicator and Structural Pest licenses

- Find recertification courses for private and commercial licenses

- Renew Commercial and Pesticide Contractor Licenses (Structural renewals coming very soon)

- Apply for a new Pesticide Contractor License

- Apply for a new RUP Dealer license

- Secure & Verifiable documents (coming very soon)

Does Georgia have reciprocal pesticide applicator license agreements with other states?

Georgia does reciprocate with other states on certain categories. Anyone needing more information on this can call Ag Inputs – Pesticide Section at 404-656-4958.

Identifying & controlling different mosquito species

Rosmarie Kelly, Public Health Entomologist, Georgia Department of Public Health

Rosmarie Kelly, Public Health Entomologist, Georgia Department of Public Health

The first step in controlling the mosquito species which are causing your client problems is to identify the local species. Quite often, not all methods of control will work well for all species. Knowing which species are the issue can help you determine future control methods.

So, how do you determine which species are active at any given time in your area? The best method is to set out light traps in the area, collect the mosquitoes, and identify them. If this is done in a systematic way, it is possible to develop a database of local mosquito species that will aid you in determining the best method of control at any given time.

Is this always feasible? Unfortunately, no. However, depending on where your client lives, some of this information may be available from other sources. Municipal mosquito control programs in Georgia rarely have sufficient funding to do mosquito surveillance. However, there are a few programs that do collect surveillance data and may be willing to share information.

Mosquito information is available through the Georgia Mosquito Control Association. Also see the other resources listed at the end of this article.

The very least that should be done is to determine if the mosquito causing the problem is Aedes albopictus, the Asian tiger mosquito. Asian tiger mosquitoes are small, aggressive, day-biting mosquitoes with black and white striped legs.

Since they do not fly far from their breeding ground, Asian tiger mosquitoes can be controlled through a combination of source reduction (eliminating breeding sites) and barrier spray (application of pesticide to vegetation where mosquitoes rest). Not all mosquitoes will rest locally after biting, so barrier spray may not be as effective for all species but it works well for Asian tiger mosquitoes.

The most important reason to understand which mosquito species are causing problems at any given time is to assist with educating the client. People tend to believe that all mosquitoes are the same, and often have unrealistic ideas about their control. If you are well informed, it can help you when discussing control issues with the client and assist in keeping the client happy with your control program.

There are control situations that are better handled by commercial mosquito control companies. Having a list of local commercial applicators can be useful to a municipal program.

Resources are available to assist with mosquito surveillance and identification. Check out:

Simple Key to Some Common Georgia Mosquitoes

Best Management Practices for Integrated Mosquito Management

Georgia Mosquito Control Association

American Mosquito Control Association

The Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory at the University of Florida offers an Advanced Mosquito Identification and Certification Course (http://mosquito.ifas.ufl.edu/Advanced_Mosquito_ID_Course.htm).

The Georgia Department of Public Health has offered at least one mosquito ID course every year since 2002, and hopes to continue this tradition depending on funding. Watch the Pest Control Alerts training page for these classes or other upcoming training.

The various mosquito control products vendors not only offer equipment calibration, they also offer training opportunities.

Mosquitoes Modified to Create Only Male Offspring Could Help Eradicate Malaria

Scientists have modified mosquitoes to produce sperm that will only create males, pioneering a fresh approach to eradicating malaria.

In a study published in the journal Nature Communications, scientists from Imperial College London have tested a new genetic method that distorts the sex ratio of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes, the main transmitters of the malaria parasite, so that the female mosquitoes that bite and pass the disease to humans are no longer produced.

Demise of Small Mosquito Control Programs (and the Effect on West Nile Virus Transmission)

State public health officials in Georgia support an integrated approach for mosquito control. Local officials can contact the Department of Public Health for more information about how to conduct an integrated program in their counties.

Learn more at the Georgia Department of Public Health Web Page.

Also check out the Georgia Mosquito Control Association website.

Summary of an article by Dr. Rosmarie Kelly, Georgia Department of Public Health Read the entire article here

A number of published reports suggest that mosquito control programs, and especially those using Integrated Mosquito Management techniques, are needed to reduce the risk of arboviral (West Nile Virus and some other mosquito vectored diseases) transmission at the local level. A study from Michigan indicated that people in communities with no mosquito control program had a tenfold greater risk of West Nile fever/encephalitis than those in areas where mosquitoes were controlled http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/conf/pdf/Walker_6_04.pdf

A Chicago area study suggested that mosquito control programs made a difference in WNV infection rates. The Des Plaines Valley District, with an intensive program to kill mosquito larvae, had four West Nile fever/encephalitis cases per 100,000 people, while the North Shore District, with a less ambitious program, had 51 cases per 100,000. This study showed that the program with the most mosquito surveillance and best documented larviciding and adulticiding operations had the fewest number of West Nile fever/encephalitis cases (Tedesco, Ruizand and McLafferty 2010).

This is not new information. The efficacy of aerial insecticide applications to reduce the transmission of Saint Louis Encephalitis (SLE) virus was shown during an epidemic in Dallas, TX in 1966. This study presented evidence that infection rate is reduced as a consequence of anti-mosquito measures. Before aerial spraying there was an SLE virus infection rate of 1 in 167 mosquitoes tested. After aerial control operations the SLE virus infection rate was 1 in 28,639 mosquitoes (Hopkins et al. 1975)

So, are small programs important? There was a documented increase in vector populations after the temporary closure of Clayton County, Georgia’s mosquito control program. There was an apparent increase in the risk of West Nile fever/encephalitis based on the presence of increased numbers of vector species and the detection of an early human case of West Nile fever/encephalitis in 2010. There was also a suspected increase in nuisance species and mosquito complaints, although these data were not collected. The Clayton County program has since been re-instated and is administered by Public Works.

Since the size of mosquito populations is crucial to disease transmission, it is important to reduce these populations below transmission thresholds. Even small programs can provide a reduction in vector populations and reduce the risk of vector-borne disease transmission.

References:

Hopkins, CC et al. 1975. The epidemiology of St Louis encephalitis in Dallas, Texas in 1966. Am J Epidemiol 102: 1-15.

Tedesco C, Ruiz M, and McLafferty S. 2010. Mosquito politics: Local vector control policies and the spread of West Nile Virus in the Chicago region. Health & Place, 16 (6): 1188-1195.

Insects and Cold Weather

Elmer Gray, University of Georgia, Entomology Department

With this winter’s unusually cold temperatures, the question of how these conditions affect insects is sure to arise. It is of little surprise that our native insects can usually withstand significant cold spells, particularly those insects that occur in the heart of winter. Insect fossils indicate that some forms of insects have been in existence for over 300 million years. As a result of their long history and widespread occurrence, insects are highly adaptable and routinely exist and thrive, despite extreme weather conditions. Vast regions of the northern-most latitudes are well known for their extraordinary mosquito and black fly populations despite having extremely cold winter conditions.

The question then arises, how do insects survive such conditions? In short, insects survive in cold temperatures by adapting. Some insects, such as the Monarch Butterfly migrate to warmer areas. However, most insects use other techniques to survive the cold.

In temperate regions like Georgia, the shortening day length during the fall stimulates insects to prepare for the inevitable winter that follows. As a result, many insects overwinter in a particular life stage, such as eggs or larvae. Many mosquitoes overwinter in the egg stage, such as our common urban pest the Asian Tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), waiting for warmer temperatures and sufficient water levels to hatch in the spring. Another technique is to take advantage of protected areas, as do adult Culex mosquitoes overwintering in the underground storm drain systems. Other insects overwinter as larvae or pupae in the soil, protected from the most extreme temperatures. However, this still doesn’t answer how insects survive freezing temperatures, only to become active as warmer temperatures return.

All insects have a preferred range of temperatures at which they thrive. As the temperature drops below this range the insects become less active until they eventually cannot move. A gradual decline in temperatures, coupled with a shortening day length, serves to prepare an insect to tolerate freezing temperatures. Several factors are important to this tolerance.

The primary thing that an insect has to avoid is the formation ice crystals within their body. Ice crystals commonly form around some type of nucleus. As a result, overwintering insects commonly stop feeding so as to not have food material in their gut where ice crystals can form. This reduction in feeding will also result in a reduction in water intake.

A degree of desiccation increases the concentration of electrolytes in the insect hemolymph (blood) and tissues. In addition, insects that can tolerate the coldest of temperatures often convert glycogen to glycerol. These electrolytes and glycerol create a type of insect antifreeze. This will lower the freezing point of the insect to well below freezing, a condition described as supercooling. When this occurs, the insect can withstand extremely cold temperatures for extended periods.

However, at some point insects will suffer increased mortality, possibly due to desiccation, toxicity or starvation. Nevertheless, insects are well adapted to survive freezing temperatures, especially after a few 100 million years to perfect their systems. It is generally assumed that introduced pest insects from sub- and tropical areas would be more susceptible to extended cold spells, but depending on their ability to find local refuges and their numbers and adaptability, they likely will remain viable and persist as pests as well.

In summary, entomologists don’t expect the cold winter to have a significant impact on insect populations this spring. Local conditions related to moisture and overall seasonal temperatures (early spring/late spring) will play a much more important role in insect numbers as we move from winter to summer and prepare for the insects that will be sure to follow.

Online Training for the Pest Control Industry

Past trainings and webinars have been recorded and made available online. For more information, click on the links below. Not all webinars originate from Georgia, so not all information may be pertinent to our area.

Past trainings and webinars have been recorded and made available online. For more information, click on the links below. Not all webinars originate from Georgia, so not all information may be pertinent to our area.

This website lists the available online trainings.

Are Those Itsy Bitsy Spiders Good or Bad? May 2, 2014

Dealing with People Who Think They are Infested with Invisible Bugs February 19, 2014

Dr. Nancy Hinkle, Professor of Medical-Veterinary Entomology at the University of Georgia.

The presentation is available as a podcast at these two sites. You may need to download QuickTime to view the video.

https://podcasting.usg.edu/4DCGI/Podcasting/GDIG/Episodes/7449/63351365.mp4

https://podcasting.usg.edu/4dcgi/podcasting/episode.html?episode_str=63351365

Home Invaders (Kudzu bugs and others) October 2, 2013

Dr Dan Suiter, Professor and Program Leader-Urban Entomology, University of Georgia.

Elmer Gray, UGA Entomology Department.

The Bugs That Won’t Go Away: Your role in delusional infestation March 27, 2013

Dr Nancy Hinkle, UGA Entomologist

Dr. Peter Lepping, Consultant Psychiatrist, Visiting Professor at Glyndwr University in Wrexham, Wales

Ant Control Made Easy May 17, 2012

How Can You Tell if You Have Odorous House Ants? Dr. Karen Vail, University of Tennessee

Understanding the Biology and Behavior of Carpenter Ants Dr. Dan Suiter, University of Georgia

Managing Problems with Pharaoh Ants Dr. Michael Merchant, Texas A&M University

Fire Ant Control Made Easy May 10, 2012

How Can You Tell if You Have Fire Ants? Dr. Jason Oliver, Tennessee State University

Understanding the Biology and Behavior of Fire Ants, Vicky Bertagnolli-Heller, Clemson University

Managing Imported Fire Ants, Dr. Bastiaan Drees, Professor, Texas A&M University

Biological Control of Fire Ants, Dr. Lawrence Graham, Auburn University