Pre-emergence Annual Bluegrass Control in Turf

Patrick McCullough, Extension Weed Specialist, University of Georgia

Edited from a more complete article which can be found here.

Annual bluegrass (Poa annua L.) is a problem winter annual weed. Contrary to its name, both annual (live for one season) and perennial (live for many seasons) populations of annual bluegrass may be found in turf.

Annual bluegrass seed germinates in late summer/early fall once soil temperatures fall below 70° F. Annual bluegrass may out-compete other turf species during late fall and early spring. Annual bluegrass often dies from summer stresses but may survive if irrigated – especially the perennial biotypes.

Cultural Control of Annual Bluegrass

Irrigate deeply and infrequently to encourage turfgrass root development and improve the ability of turf to compete with annual bluegrass. Overwatering, especially in shady areas, may encourage annual bluegrass invasion.

Avoid soil compaction. Core aerate during active turf growth to encourage quick recovery. For cool-season grasses, time aerfications before annual bluegrass germinates.

Reduce nitrogen fertilization during peak annual bluegrass germination and periods of vigorous growth. Fertilizing dormant turfgrasses when annual bluegrass is actively growing may make infestations worse.

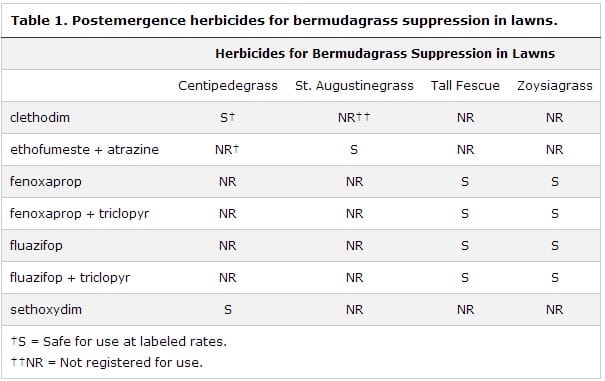

Use the proper mowing height, frequency, and equipment for your turfgrass (Table 1). Raise the turf mowing height during peak annual bluegrass germination.

Mow turfgrass frequently during periods of vigorous growth to prevent scalping. Returning clippings recycles nutrients to the soil but clippings may need to be removed when annual bluegrass is producing seedheads to reduce the spread of viable seed.

Prevention Using Pre-emergence Herbicides (See Table 2)

Preemergence herbicides may prevent annual bluegrass establishment from seed. However, preemergence herbicides will not eradicate established plants and will not effectively control perennial biotypes of annual bluegrass from spreading vegetatively. Application timing of preemergence herbicides for annual bluegrass control is very important. Herbicides must be applied in late summer/early fall before annual bluegrass germination. A second application can be applied in winter to control later germinating plants. Fall applied preemergence herbicides should not be used if reseeding or resodding is needed to repair areas of damaged turf within several months after herbicide applications.

Several preemergence herbicides used for summer annual weed control will effectively control annual bluegrass in fall and winter (Table 2). Fall applications of herbicides such as bensulide (Betasan), dithiopyr (Dimension), flumioxazin (Sureguard), oxadiazon (Ronstar, Starfighter), pendimethalin (Pendulum, others), and prodiamine (Barricade, others) may effectively control annual bluegrass. Indaziflam (Specticle) provides excellent preemergence control of annual bluegrass and also provides early-postemergence control as well. Indaziflam is only labeled in warm-season turfgrasses but may provide greater application timing flexibility than dinitroaniline herbicides in fall.

Combination herbicide products are also available which may improve efficacy of applications. These products include oxadiazon plus bensulide (Anderson’s Crab and Goose), oxadiazon plus prodiamine (Regalstar), and benefin plus oryzalin (Team 2G or Team Pro). Many preemergence herbicides are available under a wide variety of trade names and formulations and turf mangers should carefully read label directions before applications.

Atrazine (Aatrex, Purge, others) and simazine (Princep, WynStar, others) are labeled for centipedegrass, zoysiagrass, St. Augustinegrass and bermudagrass. Atrazine can be applied to actively growing and dormant centipedegrass or St. Augustinegrass but bermudagrass can be injured if treated while actively growing. Both herbicides have excellent preemergence activity on annual bluegrass but soil residual is generally shorter (four to six weeks) compared to aforementioned herbicides. Several atrazine products are restricted use pesticides and turf managers should check labels for further information before use.

Mesotrione (Tenacity) is labeled for use in centipedegrass, perennial ryegrass, St. Augustinegrass (sod production only), tall fescue, and dormant bermudagrass (Table 2). Mesotrione may be applied during establishment of these grasses (except bermudagrass) and effectively controls annual broadleaf and grassy weeds. Preemergence applications of mesotrione control or suppress annual bluegrass but postemergence use is ineffective for control of established plants. Mesotrione may be applied in tank-mixtures with atrazine or simazine on centipedegrass to improve efficacy of applications.

Most preemergence herbicides will provide similar initial efficacy if applied before annual bluegrass germination and sufficient rain or irrigation is received. Preemergence herbicides require incorporation from irrigation or rainfall so that weeds may absorb the applied material. In order to effectively control annual bluegrass, preemergence herbicides must be concentrated in the soil seedbank. Retention on leaf tissue can be avoided by irrigating turf immediately after application for effective soil incorporation and herbicide activation.

Preemergence herbicide applications on non-irrigated sites have less potential for residual control, compared to irrigated turf, from product loss, poor soil incorporation, and failure to activate the herbicide. Practitioners should return clippings on non-irrigated sites to help move potential herbicides remaining on leaf tissue to the soil. If clippings are collected as part of routine maintenance, practitioners should consider returning clippings until at least half to one inch of rainfall is received. Granular products may also be applied to non-irrigated sites for better soil incorporation than liquid formulations. Granular products may be easier to handle and apply with less equipment necessary than sprayable formulations. Granular herbicides should be applied when morning dew is no longer present to avoid interference from leaf tissue.

Managing Herbicide Resistance

Repeated use of one herbicide chemistry may control annual bluegrass but resistance may develop. Herbicide resistance is the survival of a segment of the population of weeds following a herbicide dosage lethal to the normal population. Resistance occurs from repeated use of the same herbicide or mode of action over years and may be a concern with annual bluegrass.

Triazine herbicides, atrazine and simazine, have been repeatedly used for years due to the wide spectrum of weeds controlled as pre- or postemergence treatments in warm-season grasses. Resistance in weed populations has been reported with these herbicides which may contribute to inconsistent efficacy for annual bluegrass control in turf. Resistance to sulfonylureas has been reported in numerous weed species and repeated use in turfgrasses may also contribute to resistance in annual bluegrass populations.

Preemergence chemistries, such as the dinitroanalines, (benefin, oryzalin, pendamethalin and prodiamine) may have resistance among weed populations from repeated use over years. Turf managers should rotate preemergence herbicides from dinitroanilines to other modes of action to minimize resistance in annual bluegrass populations. Herbicides to consider in rotation programs from dinitroanilines would include indaziflam, ethofumesate, or oxadiazon. These chemistries offer a different mode of action than dinitroanilines but cost, label restrictions, and turfgrass tolerance may be limiting factors for using these products. Combination herbicides are also available, such as oxadiazon + prodiamine (Regalstar) and oxadiazon + bensulide (Anderson’s Crab and Goose), with more than one mode of action that effectively control annual bluegrass in turf.

Table 1. Mowing requirements for commercial turfgrasses.

|

Mowing Requirements for Turfgrasses |

| Species |

Mower Type |

Height (inches) |

Frequency (days) |

| Bermudagrass |

|

|

|

| Common |

Rotary/reel |

1 to 2 |

5 to 7 |

| Hybrid |

Rotary/reel |

0.5 to 1.5 |

3 to 4 |

| Centipedegrass |

Rotary |

1 to 2 |

5 to 10 |

| Perennial Ryegrass |

Rotary/reel |

0.5 to 2 |

3 to 7 |

| St. Augustinegrass |

Rotary |

2 to 3 |

5 to 7 |

| Tall Fescue |

Rotary |

3 |

5 to 7 |

| Zoysiagrass |

Reel |

0.5 to 2 |

3 to 7 |

Table 2. Efficacy of preemergence herbicides for annual bluegrass control in commercial turfgrasses.

| Common Name |

Trade Name (Examples) |

Efficacy |

| atrazine |

Aatrex, various |

E |

| benefin |

Balan, others |

E |

| bensulide |

Betasan, others |

F |

| dithiopyr |

Dimension |

G |

| ethofumesate |

Prograss |

G-E |

| flumioxazin |

Sureguard |

G |

| indaziflam |

Specticle |

E |

| mesotrione |

Tenacity |

F |

| oryzalin |

Surflan, others |

G |

| oxadiazon |

Ronstar, others |

G |

| pendimethalin |

Pendulum, others |

G |

| prodiamine |

Barricade, others |

E |

| pronamide |

Kerb |

E |

| simazine |

Princep, others |

E |

E = Excellent (90 to 100%), G = Good (80 to 89%), F = Fair (70 to 79%), P = Poor (<70%).

For more information

Annual Bluegrass Control in Residential Turfgrass

Annual Bluegrass Control in Non-Residential Commercial Turfgrass