Source(s): Michael T. Mengak

Armadillos in Georgia

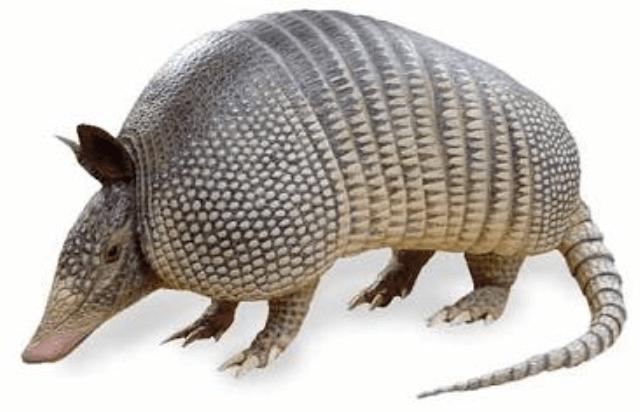

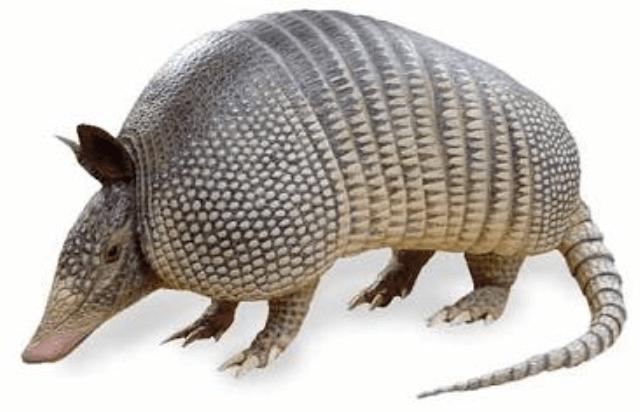

Scientists classify armadillos with anteaters and sloths. They have poorly developed teeth and limited mobility. In fact, armadillos have small, peg-like teeth that are useful for grinding their food but of little value for capturing prey. No other mammal in Georgia has bony skin plates or a “shell,” which makes the armadillo easy to identify. Just like a turtle, the shell is called a carapace.

Armadillos are common in central and southern Georgia and are moving northward. Only one species of armadillo lives in Georgia and the southeastern United States, but 20 recognized species are found throughout Central and South America. These include the giant armadillo, which can weigh up to 130 pounds, and the pink fairy armadillo, which weighs less than 4 ounces. About two million years ago a relative of the armadillo as large as a rhinoceros lived in South America, and small cousins lived as far north as Canada. These disappeared in the ice ages long before humans inhabited North America.

Taxonomy

Order Xenarthra – Armadillos, Anteaters, and Sloths

Family Dasypodidae – Armadillo

Nine-banded Armadillo – Dasypus novemcinctus

The genus name, Dasypus, is thought to be derived from a Greek word for hare or rabbit. The armadillo is so named because the Aztec word for armadillo meant turtle-rabbit. The species name, novemcinctus, refers to the nine movable bands on the middle portion of their shell or carapace. Their common name, armadillo, is derived from a Spanish word meaning “little armored one.”

Status

Armadillos are considered both an exotic species and a pest. Georgia law prohibits keeping armadillos in captivity, however. Because they are not protected in Georgia, they can be hunted or trapped throughout the year. There are no specific threats to their survival. Armadillos have few natural predators. Many are killed while trying to cross roads or highways or when feeding along roadsides.

Description

The nine-banded armadillo is about the size of an opossum or large house cat. They are 24 to 32 inches long of which 9½ to 14½ inches is tail. The larger adult males weigh between 12 and 17 pounds whereas the smaller females weigh between 8 and 13 pounds. They are brown to yellow-brown and have a few sparse hairs on their bellies. Long claws make them proficient diggers. They have 4 toes on each front foot and 5 on each back foot. The toes are spread so that a walking track looks somewhat like an opossum or raccoon. The ears are about an 1½ inches long and the snout is pig-like.

Distribution

About two million years age, a relative of the armadillo as large as a rhinoceros lived in South America. Smaller cousins lived as far north as Canada. All of these forms disappeared in the ice ages long before humans inhabited North America. At the start of the 20th century, the nine-banded armadillo was present in Texas. By the 1930s, they were in Louisiana and by 1954 they had crossed the Mississippi River heading east. In the 1950s, they were introduced into Florida and began heading north. Today, some maps (Georgia Wildlife Web: http://museum.nhm.uga.edu/gawildlife/ gaww.html) show them to be restricted to South Georgia but, in fact, they are present as far north as Athens and Rome, Georgia. They occur throughout the South from Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas through Missouri, eastern Tennessee and into South Carolina. They are currently absent from North Carolina but are likely to continue to move northward along the coast and into the Piedmont. Because they do not tolerate cold temperatures (below about 36 degrees F), several studies suggest that farther northward migration into the Appalachian Mountains will be limited.

Form and Function

The armadillo’s appearance is unique among Georgia’s mammals. The shell (carapace) is made up of scutes or bony plates attached to a tough epidermal skin layer. Since each scute overlaps slightly with the one before it, the entire shell appears to move like a telescope or accordion. The ears, underbelly and parts of the head and limbs are not covered by the shell. The head is relatively small. The skull is tubular; the lower jaw is long and slender. There are 7 or 8 teeth in each jawbone or 14-16 teeth in the lower jaw and the same number in the upper jaw. The teeth are small pegs with a single root. Armadillos can have 7-10 bands on the shell even though their name indicates nine. Males are about 25 percent heavier than females on average. Though males lack a scrotum and external testes, the sexes are easy to distinguish by the presence of four teats in females. Both sexes possess anal glands that protrude when the animal is excited. The anal glands produce a strong odor but, unlike a skunk, they do not spray.

Ecology

Armadillos dig their own burrows or use the burrow of another armadillo, tortoises or natural holes. They do not hibernate but neither can they tolerate high temperature (above about 85 degrees F). During the winter months they often are active during the warmer part of the day. During the hot summer, activity shifts to the cooler night hours. While they can remain in their burrows for several days, they do not store food or accumulate large stores of body fat, so they must eventually emerge to forage. In bad weather, they can freeze to death or starve if they are unable to locate food. Armadillos rely on a good sense of smell to locate food but have poor eyesight. They eat insects and surrounding soil and plant litter while foraging, so their droppings consist of undigested insect parts, soil and litter fragments. Droppings are about the size and shape of marbles.

Reproduction

Armadillos reach sexual maturity at about one year of age. They breed between June and August. They have delayed implantation (a step in development when the fetus attaches to the wall of the uterus), which can last for up to four months. Implantation occurs around November and gestation lasts about four months. Generally, the female produces only one litter per year. A single fertilized egg gives rise to four separate embryos. Thus each litter consists of four identical quadruplets. Fully formed young are born with their eyes open in March or April. They weigh 3-4 ounces at birth and can walk within a few hours but remain in the nest or burrow for 2-3 weeks. Then the young follow their mother while foraging. The young leave the nest at 20- 22 days (around the first or second week of June in south Georgia), drink water at 21-25 days, eat solid food at 35-42 days, eat insects at 71-74 days, and are weaned at 90-140 days. The armor plates on the young are soft and flexible at birth — not hardening to the typical adult form until July in south Georgia. The male plays no role in raising or caring for the young.

Feeding

Armadillos are largely insectivores but may consume fruit when available. Their skull, jaw and teeth are adapted to a specialized diet. Their tongue is sticky with rear facing hooks giving the tongue a rough texture. The armadillo’s diet consists mainly of invertebrates including insects (beetles, wasps, moth larvae) and also ants, millipedes, centipedes, snails, leeches, and earthworms. The exact composition varies by season, availability and geographic locations. Studies show they also consume fruit, seeds and other vegetable matter. They have been reported to consume newborn rabbits and at least one robin. It is unknown if they merely found these animals dead or not. Other items known to be consumed by armadillo include salamanders, toads, frogs, lizards, skinks, and small snakes.

University of Georgia researchers studying armadillos on Cumberland Island found that, although their diets varied seasonally, 99 percent of their diet consisted of beetle (Coleoptera) larvae, and ant and wasp (Hymenoptera) eggs, pupae and adults. White grubs and wireworms were the most frequently consumed larvae throughout the year. Armadillos were also found to consume earthworms, crabs, crayfish, butterfly and moth larvae, fruits and vertebrates. In addition, 60 out of 171 armadillo (35%) in the sample ate fruit. Grapes, saw palmetto, greenbrier and Carolina laurel cherry were most common in the diet. Armadillos also occasionally consumed spadefoot toad, five-lined skink, green anole, eastern fence lizard, rough green snake, and various snake and lizard eggs. Using remote cameras to study nest predation, several studies have shown that armadillos consume quail eggs. Other observers report that sea turtle eggs are eaten.

Feeding activity, such as digging, is often considered a nuisance, although consumption of ants, including fire ants, and white grubs may be beneficial in other ways. Small invertebrates are swallowed whole while large items are chewed. They will hold and tear apart larger food items with their claws and feet. In one study in Alabama, nearly every fire ant mound on the study site showed evidence of disturbance by armadillo. They seem undeterred by the bite of the fire ant. Armadillos have been observed tearing the bark from fallen trees, presumably to feed on the insects (beetles and termites) in the decaying wood. They move slowly while feeding and locate food items by smell. The diet shifts to fruits in the summer and fall as these items are often abundant in southern U.S. forests.

Behavior

Armadillos spend most of their active time outside the burrow feeding. They move slowly – traveling between 0.15 and 0.65 miles per hour — often in an erratic, wandering pattern. Often grunting like pigs and with their snouts to the ground, they forage by smell and possibly sound. They often use their sticky tongue to probe holes searching for food, but they are also powerful diggers. Foraging pits are up to 5 inches deep and are often found in moist soil. Periodically they will stop foraging, stand upright on their hind legs balancing with their tails, and sniff the air. They also take low hanging fruits from this posture.

Armadillos mark their territory with secretions from the anal gland. Individuals may be able to recognize others through scent marking. When alarmed they can run quickly. They have a habit of leaping vertically like a bucking horse before running away in a surprising burst of speed. The anal gland’s strong odor and the sudden leaping motion may momentarily startle a predator, possibly allowing the armadillo to escape.

Contrary to popular folklore, the nine-banded armadillo cannot curl into a ball to protect itself. Armadillos are good climbers and readily climb fences although they are not known to climb trees. They often use fallen and leaning logs and trees to escape rising water along streams and rivers. Armadillos can cross water by either swimming in a typical, dog-paddle motion or walking on the bottom while holding their breath. Buoyancy is increased by ingesting air into the stomach and intestines. Armadillos can cross small water bodies by holding their breath and walking underwater for short distances. One armadillo swam across a river 140 yards wide. Having a specific gravity of 1.06 helps, since it makes them heavier than water. Armadillo are known to take mud baths on hot days, perhaps to remove parasites or to coat themselves in cooling mud.

They make a variety of low grunting sounds when feeding or to call young to mother. Other sounds are described as “wheezy grunt,” “pig-like sound,” “buzzing noise” and a “weak purring” made by very young armadillo while attempting to nurse. They are capable of learning simple tasks in a laboratory, such as recognizing patterns in a Y-maze. They are primarily solitary animals except during brief periods for mating and mother-young groups.

Habitat

Armadillos prefer habitat near streams but avoid excessively wet or dry extremes. Soil type is important due to their burrowing. They prefer sandy or clay soils. Armadillos can be found in pine forests, hardwood woodlands, grass prairies, salt marsh and coastal dunes. Human created habitats such as pasture, cemeteries, parks, golf courses, plant nurseries and crop lands also provide suitable habitat. They also forage along roadsides. While foraging, armadillos always seem to know where they are and, if alarmed, often take a direct route to the safety of a nearby burrow or tangle of roots and briars. They usually dig their own burrows. Burrow entrances will be 8 to 10 inches across and range from 2 to 24 feet long averaging 3 to 4 feet. The burrow entrance is often concealed among clumps of vegetation, fallen logs or under buildings. Each armadillo may have 5 to 10 burrows. The average number of different burrows used per individual armadillo was 10.9. Other animals will use armadillo burrows including rabbits, opossums, mink, cotton rats, striped skunks, burrowing owls, and the eastern indigo snake.

Occasionally, armadillos will cohabit with other animals. Armadillo do not always dig a burrow; some will build nests out of dry grass. These nests resemble small haystacks and are often used in areas of wet soil. On Cumberland Island, University of Georgia researchers found that 75 per-cent of all dens were under saw palmetto plants. An individual’s home range varies from 1.5 to 22.5 acres. The home range size is smaller for the armadillo than for similar sized animals. Researchers at the University of Georgia found that armadillos on Cumberland Island had a home range of 13 acres in summer and only 4 acres in winter. Armadillos spent 65 percent of their time in burrows in winter compared to only 29 percent in summer.

Enemies

Armadillos have few wild predators, but coyotes, dogs, black bears, bobcats, cougars, foxes and raccoons are reported to catch and kill armadillos in places where these predators occur. Hawks, owls and feral pigs may prey on armadillo young. One study noted a decline in armadillo numbers as feral pig populations increased. Humans and highways are significant sources of mortality in many areas. One study in Florida, however, found no juveniles in a road-killed sample.

Populations

The sex ratio by litter is 1 male litter (= 4 identical quadruplets) per 0.78 female litters in Florida. Armadillos probably live 6 to 7 years in the wild. Population density is about one animal per 4 acres but could range as high as two animals per acre.

General

Their flesh is tasty and often eaten by people. Weather, especially cold winters, may be the most effective barrier to northern range expansion. Their normal body temperature is 92-95 degrees F.

Disease

Armadillos may carry diseases transmissible to humans, but reports are rare. Armadillos can acquire leprosy and are used in medical research to study this disease. Only two cases are known in which a human contracted leprosy from wild armadillos. Both cases are from Texas, and the transmission occurred by consuming raw or undercooked armadillo meat. There are no reported positive cases in Georgia, Alabama or Florida. One wild armadillo in Texas was reported to have rabies but no known transmission to humans has occurred. Armadillos on Cumberland Island, Georgia, had between 0 and 3 species of parasitic worms per individual. The average was 14 worms per individual armadillo but the impact of these parasites on the health of the animal is unknown.

Economic Value

One study in Texas from 1975-1979 put the total amount of damage at $20,000 for a limited area but did not specify the type of damage. In Georgia, 78 percent of county agents reported receiving requests for information regarding armadillos, and that armadillo complaints accounted for nearly 11 percent of all animal complaints they received each year. No dollar value was attached to the damage complaints, however. Furthermore, the monetary value of damage done to vehicles is not known.

Damage occurs to lawns and landscape due to digging for insects and other food items. Shallow holes 1 to 3 inches deep and 3 to 5 inches wide, usually shaped like an inverted cone, are the most common landowner complaints. Armadillos can uproot flowers and other plantings through their foraging. Damage is generally local and of a nuisance variety more than a large scale economic loss.

Legal Aspects

Armadillos are not protected in Georgia. There are no season or harvest restrictions.

Control to Reduce

Armadillo can be controlled by trapping. Wire cage live traps measuring at least 10 x 12 x 32 inches are recommended. Use of wings, constructed of 1 x 6 inch lumber in various lengths and placed in a V-arrangement in front of the trap can help to “funnel” the armadillo into the trap. Setting traps along natural barriers like logs or the side of a building increases capture success. Placing the trap in front of a burrow entrance is better than random placement in the environment. No bait, lure or attractant has been shown to be effective in increasing capture success, although there are numerous report of baits used with varying success. No repellents are registered for use with armadillo. No toxicants (poisons) are registered for use. Pesticide use to reduce insect populations in landscape settings may be effective. No fumigants are registered for use to control armadillo. Shooting is an effective control technique. Use a .22 caliber rifle in a safe and legal manner. Check city and county ordinances before discharging weapons. Always practice safe gun handling procedures.

Management to Enhance

Management activities are usually directed at control and elimination rather than enhancement.

Human Use

Native American Use – None. Armadillos are widely used (and considered a delicacy) by many cultures in Central and South America. Colonists View – None.

Center Publication Number: 196