Info taken from the EcoIPM website and the SE Ornamental Horticulture & IPM website

Gloomy scale

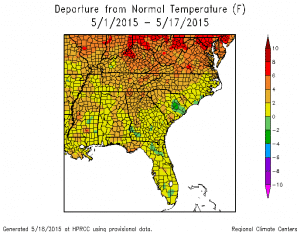

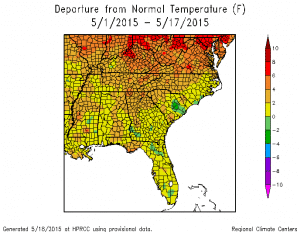

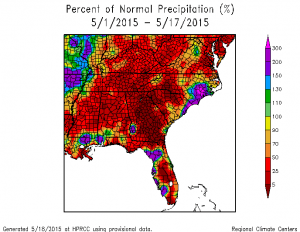

Gloomy scale, Melanaspis tenebricosa, is an armored scale that feeds on maples and other tree species. It becomes very abundant on red maples on streets and in landscapes and can cause branch dieback and tree death in some cases. It is not unusual to find trees with nearly 100% of their trunk covered in scale. Street trees are particularly prone to gloomy scale. Crawlers of this scale are active now and can be seen on bark and under scale covers. One of the reasons we have found this to be such a pest is that female gloomy scales produce about 3 times as many eggs when they live on relatively warm trees (like in a parking lot) than when they live on cooler trees (like in a shady yard). This amazing work is outlined in a recent paper by Adam Dale.

Control of this scale is complicated because crawlers emerge over 6-8 weeks so it is impossible to treat all the crawlers at once with horticultural oil or other contact insecticide. This is different than in other scales, such as euonymus scale, in which all crawlers are produced within a narrow window of 2 weeks or so. Adam Dale took a video of some gloomy scale crawlers so you can get an idea of how tiny and nondescript they are. This may also give you an idea of why scales are so vulnerable at this stage to the environment, predators, and insecticides like horticultural oil. Once they produce their thick waxy cover they are much less vulnerable to all these factors.