Paul Pugliese, Agriculture & natural resources agent for the University of Georgia Cooperative Extension office in Bartow County

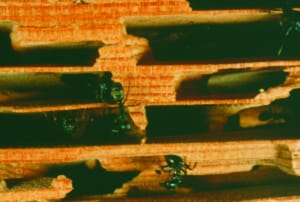

With their metallic copper and blue-green bodies and bronze wings, Japanese beetles might be considered beautiful if not for the damage they cause. The plentiful beetles munch holes into the leaves of landscape plants leaving what is often described as skeletal remains.

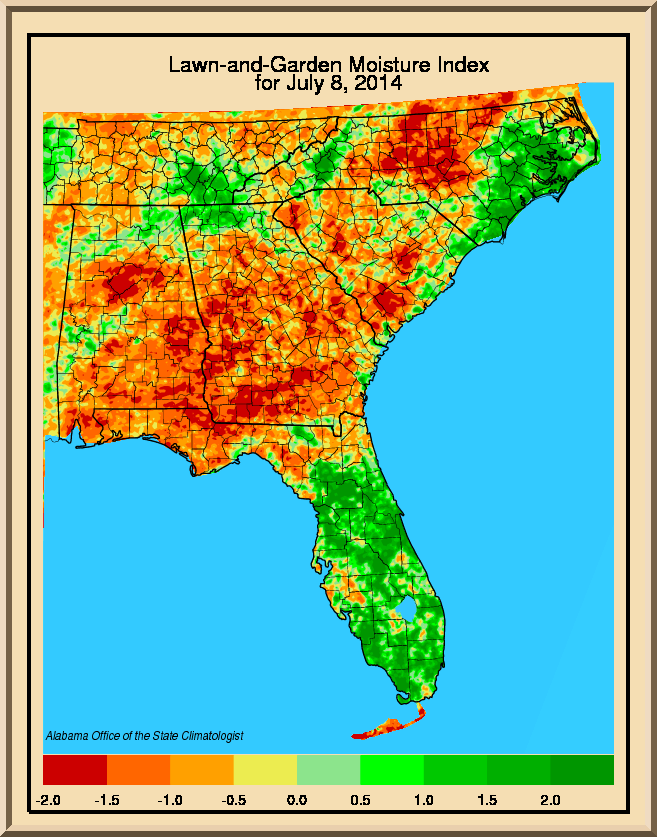

Prior to last year, Georgia had a few years of drought and unusually mild winters. The warm, dry soil conditions were not conducive for Japanese beetle grubs to survive over the fall and winter throughout most of Georgia. This gave Georgia gardeners and landscapes a nice reprieve from the pest and its damage.

Perfect conditions return

This past winter was ideal for Japanese beetle grubs and home and commercial gardeners are suffering through a resurgence of adult beetles this summer. The severity of local Japanese beetle populations varies depending on temperature and soil moisture. Most surveys indicate that Japanese beetles do not occur further south than the “fall line” between Macon and Augusta in Georgia. Yet, they can be found as far north as Canada.

If you’ve fought Japanese Beetles before, there’s a good chance they will return to your landscape – especially if your have some of their preferred plants. Japanese beetles feed on more than 300 species of broad-leaved plants but prefer about 50 species. Commonly attacked hosts include peach, cultivated and wild grapes, raspberry, plum, roses, apple, cherry, corn, hibiscus, hollyhock, dahlia, zinnia, elm, horse chestnut, linden, willow, crape myrtle, elder, evening primrose and sassafras.

They love leaves

The good news is the beetles only affect the leaves of trees and shrubs, so healthy plants can tolerate significant leaf loss without long-term consequences.

Adult Japanese beetles live four to six weeks, lay eggs (mostly in mid-August) and die. If the soil is sufficiently moist, the eggs will swell and produce larvae in about two weeks. The rest of the year, the beetles live underground in a larval stage feeding on the roots of grass and other plants before maturing into adult beetles in the summer.

Japanese beetle larvae are plump, C-shaped white grubs often seen in the spring when garden soil is first tilled. The grubs need soil moisture to survive the winter. Frequently irrigated lawns and landscapes tend to have higher grub populations.

Adult beetles emerge from the soil and begin seeking out plants for food in late May and early June. The first round of beetles are known as “scouts” because they find a good food source and release pheromone scents to attract more beetles. The masses then gather to feed and mate.

Control the first ones!

The key is to catch the early arrivers as soon as possible. Handpick or knock adult beetles off plants and drown them in soapy water. This is an effective control option for managing small infestations and preventing them from attracting more beetles.

Pheromone lure traps are not recommended for general Japanese beetle control in a small garden. They tend to attract more beetles to the area than would normally be present. Trapping should be done in areas away from gardens or landscapes to lure beetles away from desired plants.

Adult beetles can be controlled with over-the-counter insecticides. During heavy beetle outbreaks, sprays may be needed every seven to ten days to protect high-value, specimen plants like roses. A single application of a longer-lasting systemic insecticide, like imidacloprid, needs to be made 20 days before adult Japanese beetles are expected — usually around mid-May. Most systemic treatment options are not labeled for use on plants that produce edible fruits. Read and follow pesticide label’s application rates and safety precautions.

Controlling the grub stage generally has little effect on the overall damage caused by adult beetles, since adults can fly into your landscape from up to a mile away. Most homeowners rarely have grub populations large enough to cause damage to home lawns. Treatment may be necessary if more than five to ten grubs per square foot are present in lawns. Late summer and early fall insecticide applications are most effective at killing young grubs.