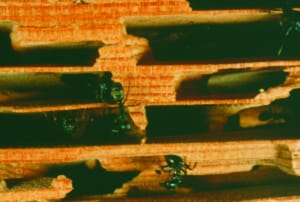

This disease is Bot canker. Bright, rust-colored branches and yellowing or browning of shoots or branches are the first observed symptoms. Closer inspection reveals the presence of sunken, girdling cankers at the base of the dead shoot or branch. Sometimes, the main trunk shows cankers that might extend for a foot or more in length. These cankers rarely girdle the trunk, but they will kill branches that may be encompassed by the canker as it grows. Read more info in the following publication including disease management.

Diseases of Leyland Cypress in the Landscape

See Entire Publication

Authors – Alfredo Martinez, UGA Plant Pathologist, Jean Williams-Woodward, UGA Plant Pathologist and Mila Pearce, Former UGA IPM Homeowner Specialist

Leyland cypress has become one of the most widely used plants in commercial and residential landscapes across Georgia as a formal hedge, screen, buffer strip, or wind barrier. The tree is best suited for fertile, well-drained soils. However, when young, the tree will grow up to 3-4 feet per year, even in poor soils. The tree will ultimately attain a majestic height of up to 40 feet.

Leyland cypress is considered relatively pest-free. However, because of its relatively shallow root system, and because they are often planted too close together and in poorly drained soils, Leyland cypress is prone to root rot and several damaging canker diseases, especially during periods of prolonged drought. Disease management is, therefore, a consideration for Leyland cypress.

This UGA Publication discusses several Leyland Cypress diseases and their management.