An excerpt taken from the publication Bermudagrass Control in Southern Lawns by Patrick McCullough, UGA Extension Weed Specialist

Find the entire publication here

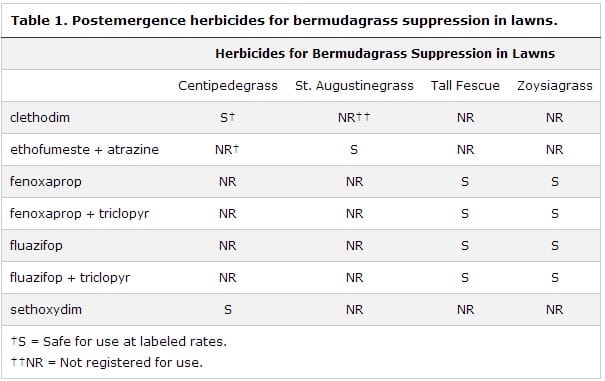

Postemergence Herbicide Control

Postemergence herbicides may be applied to suppress bermudagrass populations and reduce competition with desirable turfgrasses. Repeat applications of selective herbicides are needed for best results but may be injurious to the desirable species. Furthermore, tolerance to herbicides may vary by turfgrass cultivar and end-users should consult with local Extension specialists for application rates and recommendations.

Bermudagrass Control in Centipedegrass

Centipedegrass is a popular low-maintenance lawn species in Georgia. Centipedegrass generally has slower growth than bermudagrass with less potential for competition during the summer. Clethodim (Envoy, others) and sethoxydim (Segment, others) are cyclohexenadione herbicides that inhibit lipid synthesis in grassy weeds. Sensitive species exhibit leaf injury with reddish discoloration before significant necrosis.

Bermudagrass is sensitive to both clethodim and sethoxydim and repeat applications may suppress populations in centipedegrass. Turf managers should schedule applications approximately every three weeks during active growth. For best results, add a nonionic surfactant at 0.25% v/v with clethodim to enhance spray retention and apply no sooner than three weeks after spring green up. Certain sethoxydim products (e.g., Segment) may have a built-in adjuvant already mixed in the formulation and the addition of a surfactant is not required. For both herbicides, turf managers should avoid mowing one week before or after treatment.

Bermudagrass Control in St. Augustinegrass

St. Augustinegrass is a major warm-season turfgrass used for lawns in southern Georgia. St. Augustinegrass has desirable heat and drought tolerance but is sensitive to many herbicides. Selective herbicides for controlling grassy weeds, such as crabgrass and goosegrass, are limited in St. Augustinegrass lawns. Bermudagrass infestations are also difficult to manage.

St. Augustinegrass has good tolerance to ethofumesate (PoaConstrictor, Prograss), which may be used in combination with atrazine to control bermudagrass. Ethofumesate is an unclassified herbicide that has postemergence activity for grassy and broadleaf weed control in nonresidential St. Augustinegrass and cool-season grasses. Ethofumesate has several toxic effects in susceptible species, such as bermudagrass, but arrested cell division appears to be the primary mechanism of selectivity.

Atrazine inhibits photosynthesis in susceptible weeds and is in the triazine herbicide family. Triazines interfere with electron transport during photosynthesis and eventually lead to cell membrane destruction and cellular leakage. Susceptible weeds initially exhibit chlorosis on leaf margins. Actively growing bermudagrass is sensitive to atrazine applications and its addition to ethofumesate treatments provides postemergence and some residual control of bermudagrass. Atrazine alone may provide some bermudagrass suppression but does not provide long-term control.

Applications of ethofumesate with atrazine should be initiated during bermudagrass spring green up. Herbicide regimens that begin on actively growing bermudagrass in summer will likely be ineffective. St. Augustinegrass often responds to applications with stunted growth and discoloration. Repeat applications should be made after 30 days or once turf has recovered from any potential injury. See the current edition of the Georgia Pest Management Handbook for rates and further information about bermudagrass control.

Bermudagrass Control in Tall Fescue and Zoysiagrass

Fenoxaprop and fluazifop are used for postemergence grassy weed control in tall fescue and zoysiagrass. Sensitive weeds exhibit injured leaf tissue with reddish discoloration while plant nodes become necrotic and die. Theses herbicides have no activity on broadleaf weeds but provide excellent grassy weed control.

Fenoxaprop (Acclaim Extra) and fluazifop (Fusilade) may be used alone in tall fescue and zoysiagrass lawns. Fenoxaprop may also be used in residential and nonresidential Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.), perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) and other cool-season turfgrasses. Fluazifop may be used in commercial and nonresidential turf. Generally, tall fescue has good tolerance to these herbicides. There is greater potential for injury on zoysiagrass than on tall fescue from fenoxaprop or fluazifop treatments, especially fine-textured varieties.

Triclopyr (Turflon Ester, Turflon Ester Ultra) at high rates (0.75 to 1 lb ai/acre) is injurious to bermudagrass. Tank mixtures with fluazifop or fenoxaprop have been shown to reduce tall fescue and zoysiagrass injury without compromising control. The addition of an adjuvant to tank mixtures of fluazifop with new triclopyr formulations (e.g., Turflon Ester Ultra) is unnecessary and may increase turf injury.

In Georgia, initial applications of fenoxaprop or fluazifop should be scheduled around June 1 and repeated every 20 to 30 days. Fluazifop alone should be applied with a non-ionic surfactant at 0.25% v/v of spray solution. Acclaim Extra (fenoxaprop) does not require the addition of an adjuvant. See the current edition of the Georgia Pest Management Handbook for rates and application comments for fluazifop and fenoxaprop treatments for bermudagrass control in tall fescue.

Nonselective Bermudagrass Control

Spot treatments of nonselective herbicides are the most effective method for controlling bermudagrass. Glyphosate is a nonselective herbicide that is widely used for spot treatments of perennial weeds in turfgrasses. Glyphosate is a foliar-absorbed herbicide that is systemically translocated with no preemergence activity for weed control.

Spot treatments of glyphosate should be made to bermudagrass patches and surrounding areas to control any runners that may be intermingled with desirable turfgrasses. Broadcast applications can effectively renovate or kill existing vegetation but high rates and multiple applications are required to control bermudagrass. Glyphosate should be applied to actively growing bermudagrass. Repeat treatments will be required for complete control. Cultural practices that disrupt plant growth, such as vertical mowing and aerification, should be delayed for seven days after treatment.

Glyphosate requires optimum translocation in order to control bermudagrass rhizomes and plants emerging from lateral stems. Perennial grasses generally have greater translocation of photosynthate from leaves to stems in fall than spring, which increases glyphosate movement to rhizomes. Fall glyphosate applications generally control bermudagrass more effectively than summer treatments. Numerous glyphosate products are available under a wide variety of trade names.

Other information in this publication

- See the entire publication

- Bermudagrass Identification

- Preemergence Herbicide Control

- Postemergence Herbicide Control

- Bermudagrass Control in Centipedegrass

- Bermudagrass Control in St. Augustinegrass

- Bermudagrass Control in Tall Fescue and Zoysiagrass

- Nonselective Bermudagrass Control

- Literature Cited

For pesticide recommendations see the UGA Pest Management Handbook.