Taken from the publication Insecticide Basics for the Pest Management Professional

Daniel R. Suiter, UGA Department of Entomology & Michael E. Scharf, UFL Department of Entomology and Nematology

The MSDS provides specific information about a product’s toxicity and is expressed as an LD50. LD is an abbreviation for lethal dose, and 50 refers to 50 percent of the test animal’s population. An LD50, therefore, is a specific dose (or quantity) of a product known to be lethal to half (50 percent) of the test animals (typically lab rats) exposed individually to the reported dose. Because of the calculations involved in determining lethal doses, the LD50 is the most commonly reported value because it represents the most accurate average based on responses of test subjects. For example, LD50 is generally more accurate than LD25, LD75, or LD99 (the doses that are lethal to 25, 75, and 99 percent of the test population).

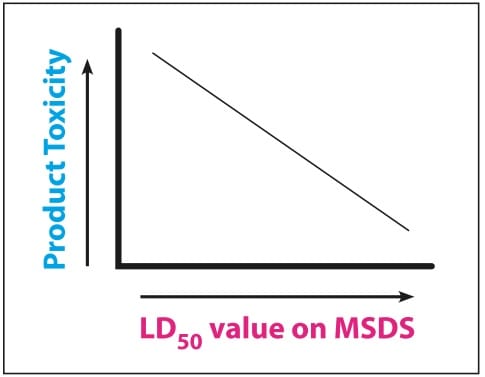

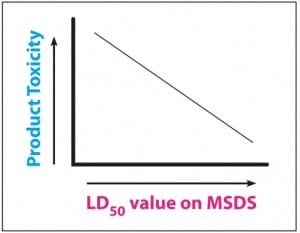

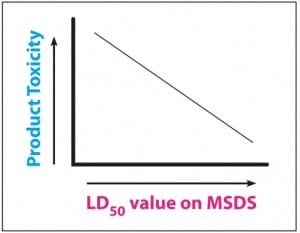

There is an inverse relationship between product toxicity and LD50 value. Products with lower LD50 values are more hazardous and pose a greater risk than products with higher LD50 values (Figure 1). For example, product A with an LD50 = 400 mg/kg is more toxic than product B with an LD50 = 600 mg/kg. In other words, to kill 50 percent of a group of test animals would require less of the more toxic product A (LD50 = 400 mg/kg) than the less toxic product B (LD50 = 600 mg/kg).

There is an inverse relationship between product toxicity and LD50 value. Products with lower LD50 values are more hazardous and pose a greater risk than products with higher LD50 values (Figure 1). For example, product A with an LD50 = 400 mg/kg is more toxic than product B with an LD50 = 600 mg/kg. In other words, to kill 50 percent of a group of test animals would require less of the more toxic product A (LD50 = 400 mg/kg) than the less toxic product B (LD50 = 600 mg/kg).

For liquid concentrates, the LD50 reported on the product’s MSDS is for the product in its concentrated form (i.e., before it’s mixed in water). For most ready-to-use products, such as most granules, baits, and dusts, the MSDS-reported LD50 is for the product in its useable form because these products can be used when purchased (i.e., they do not require further dilution or mixing).

For products that must be diluted in water, the resulting LD50 increases considerably upon dilution. The diluted product becomes much less hazardous, where hazard is a function of a product’s concentration and the amount of exposure to it. Consider the insecticide Premise 0.5 SC. In its concentrated form, it is 5.65 percent imidacloprid. When diluted in water to the usable concentration of 0.05 percent imidacloprid, the active ingredient has undergone a 113-fold reduction in concentration. As a consequence of dilution, the product’s potential hazard is reduced considerably.

How is a Product’s LD50 Determined? LD50s are most commonly determined by testing the product’s acute (single dose), oral toxicity against laboratory rats. To obtain the data necessary to calculate an LD50, a single dose (quantity) of the candidate product is force-fed to each one of a known number of healthy rats. The procedure is repeated for multiple doses of the product. At some pre-determined time after exposure, mortality is tallied. From these mortality data, statistical tests are then used to compute the product’s LD50.

Because the LD50 of all products is determined by the same methodology and in the same manner (acute, oral toxicity to laboratory rats), we are able to compare LD50 values among and between all products to determine the relative risk associated with these products.

In some cases, a product’s LD50 cannot be calculated as a single value because not enough of it can be force-fed to the test animals to induce sufficient mortality to enable the toxicologist (scientists who study how pesticides work at the molecular level) to calculate an LD50. In cases where test animals cannot be killed by force-feeding, the LD50 is often reported as >2,500, >5,000, or typically another large, even, round number. The number is usually preceded by a greater than sign (>), indicating that the product is not very toxic to laboratory rats. In such cases, toxicologists are essentially making the statement, “We cannot calculate the LD50 because we cannot give the test animals enough product to kill enough of them to allow us to calculate an LD50. Therefore, we believe that the true LD50 is larger than the highest dose we have tested.”

In addition to determining a product’s acute, oral toxicity to rats, scientists may also determine the product’s toxicity when it is absorbed through the skin (called dermal toxicity) or breathed (called inhalation toxicity). Other animals on which oral, dermal, and inhalation toxicities may be determined include mice, quail, rabbits, and mallard ducks. These additional pieces of toxicological information, and associated ecological considerations, can be found on the MSDS in a section on environmental considerations.

See the rest of the publication at Insecticide Basics for the Pest Management Professional

Do you like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube or blogs? If so, the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences may have something of interest for you!

Do you like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube or blogs? If so, the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences may have something of interest for you!